After a break over the summer, we will be picking our OpenITI manuscript reading group back up for the fall academic semester, with a somewhat different iteration from previous semesters. In the past we have taken a somewhat ad hoc approach to our reading material, focusing on one manuscript for a few weeks at a time, an enjoyable approach that allowed us to cover many different genres, periods, scripts, and texts. However, this year we are taking a different tack, one that will be a supporting component of a larger project. Our focus this semester will be on reading through a single, albeit pretty monumental, manuscript, one of the volumes of a multi-volume “library between two (well, actually six in this case!) covers” compiled by the South Asian early modern scholar Muḥammad Khalīlallāh al-Shaṭṭārī and titled Safīnat al-baḥr al-muḥīṭ. Fully describing this work in the space of a blog would be impossible, indeed one of the goals of our larger project is to provide a thorough critical description of the Safīnat in all of its complexity and in terms of the origins and trajectories of the texts contained within it; the selection process for compilation; the internal logics and orders of texts, paratexts, visual and organization material that make up the work; the theory of readership that animates the work; and the later reception and use history of the volumes, which have today ended up far apart in different parts of the world.

Before describing this larger project that we are in the early stages of launching, here’s what we’re envisioning for this fall’s reading group, one which anyone out there interested in Islamicate manuscript is welcome to join: while we cannot read the entirety of this text in one semester (and indeed finding ways within the DH toolkit to “read” the text at scale is part of our larger project’s ambit), we can take “soundings,” getting a feel for the contents of different sections, looking at how commentary, notations, and other paratextual elements went together with “main” texts (and whether we ought to even talk of main and marginal texts in all cases), and so forth. As we read we will try to work out what the experience of reading such texts in the early modern world might have been like—how a reader might have selected particular texts, read other texts in conjunction with one another, worked out relationships, genres, and so forth. Think of it as a kind of experimental or participatory archeology of the book, focusing not just on our encounter with the semantic content but also the codicological affordances, the structures and arrangements, and all of the paratextual guides and indicators al-Shaṭṭārī included.

We will start with the compiler’s introduction to the work, which describes his reason for writing and his de facto theory of readership, then select additional sections to read, transcribe, and, in some cases, translate into English (for a list of many, though not at all, texts contained within this volume see the Qalamos entry). The texts are in Persian and, to a lesser extent, Arabic, so readers of either or both languages are especially welcome—and if you are a learner (which we all are to some extent when this sort of material is considered) this will be a great opportunity to practice your Persian and/or Arabic, while also encountering a range of hands and script styles, many of which are represented within the work’s covers. We may at some points this semester and next read as supplementary material relevant secondary literature works, which will be posted in advance, alongside our weekly journey through the Safīnat.

Our sessions will be held via Zoom on Tuesday mornings from 10 am Eastern US time to 11:30 am or so, not going past 12 pm. If you would like to join, the best way would be to email me directly at jallen22@umd.edu and I will send you a Calendar invite with the Zoom link. We also have a Slack workspace that participants are encouraged to join, wherein weekly sessions will be outlined in advance in terms of sections to be read.

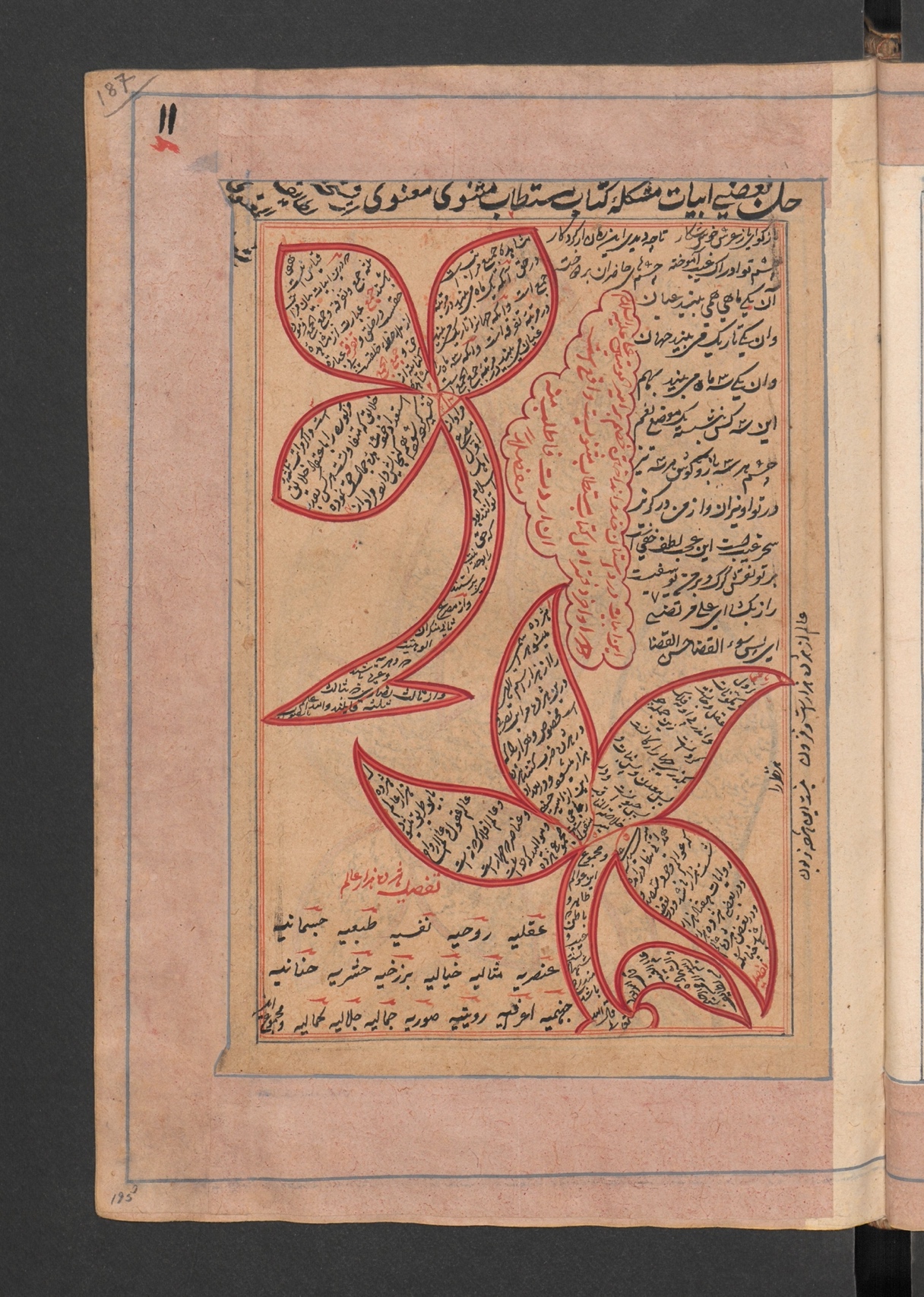

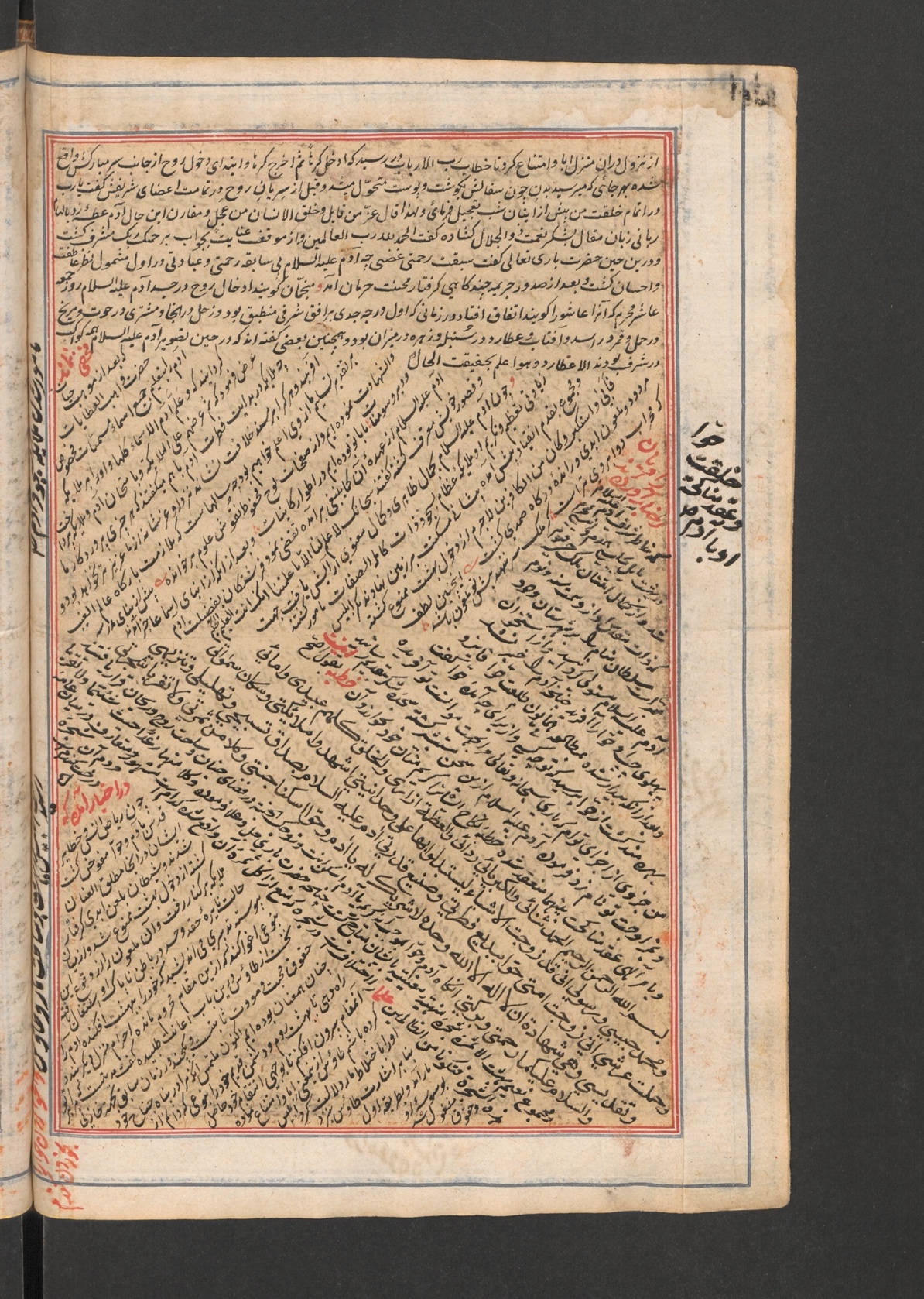

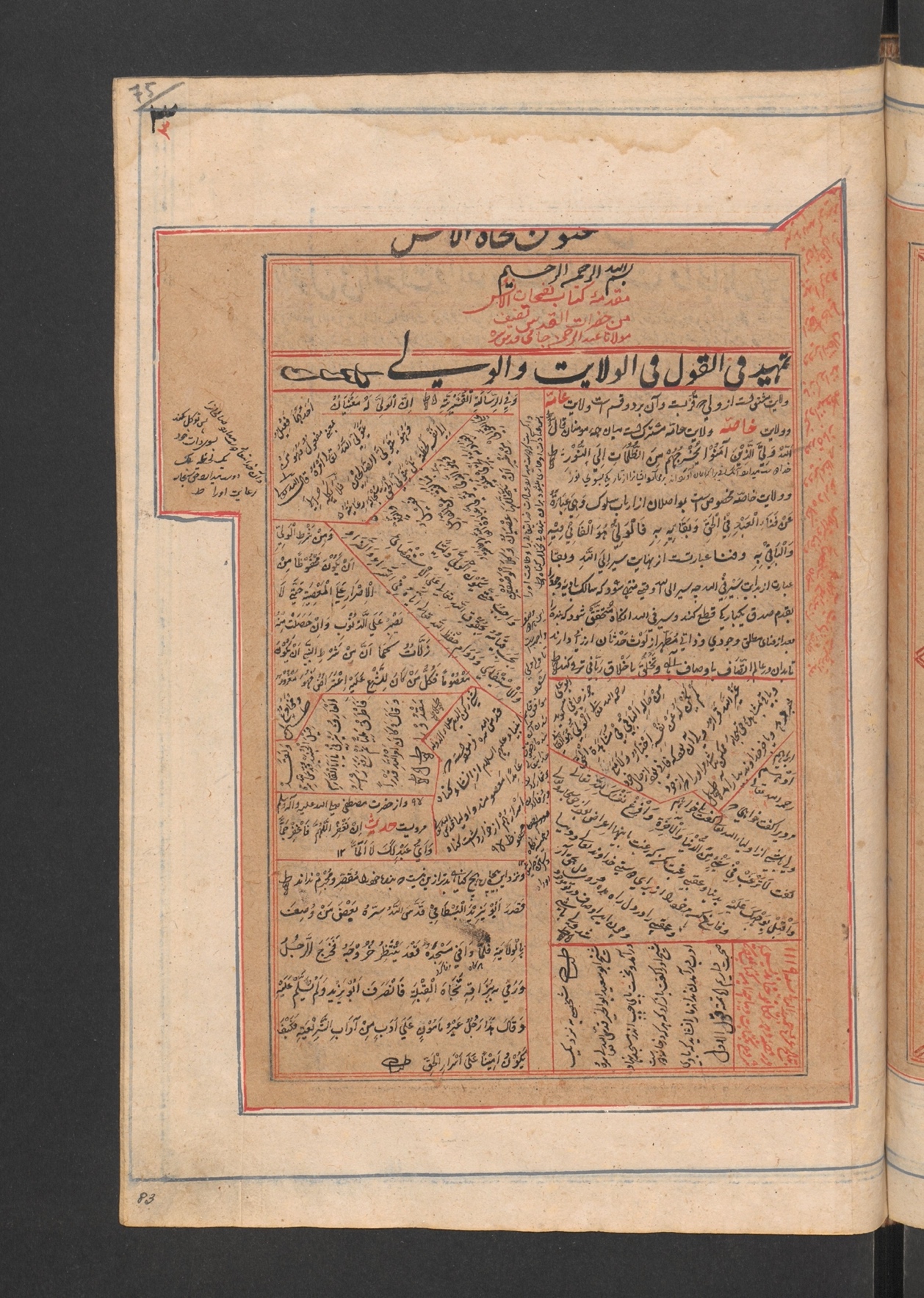

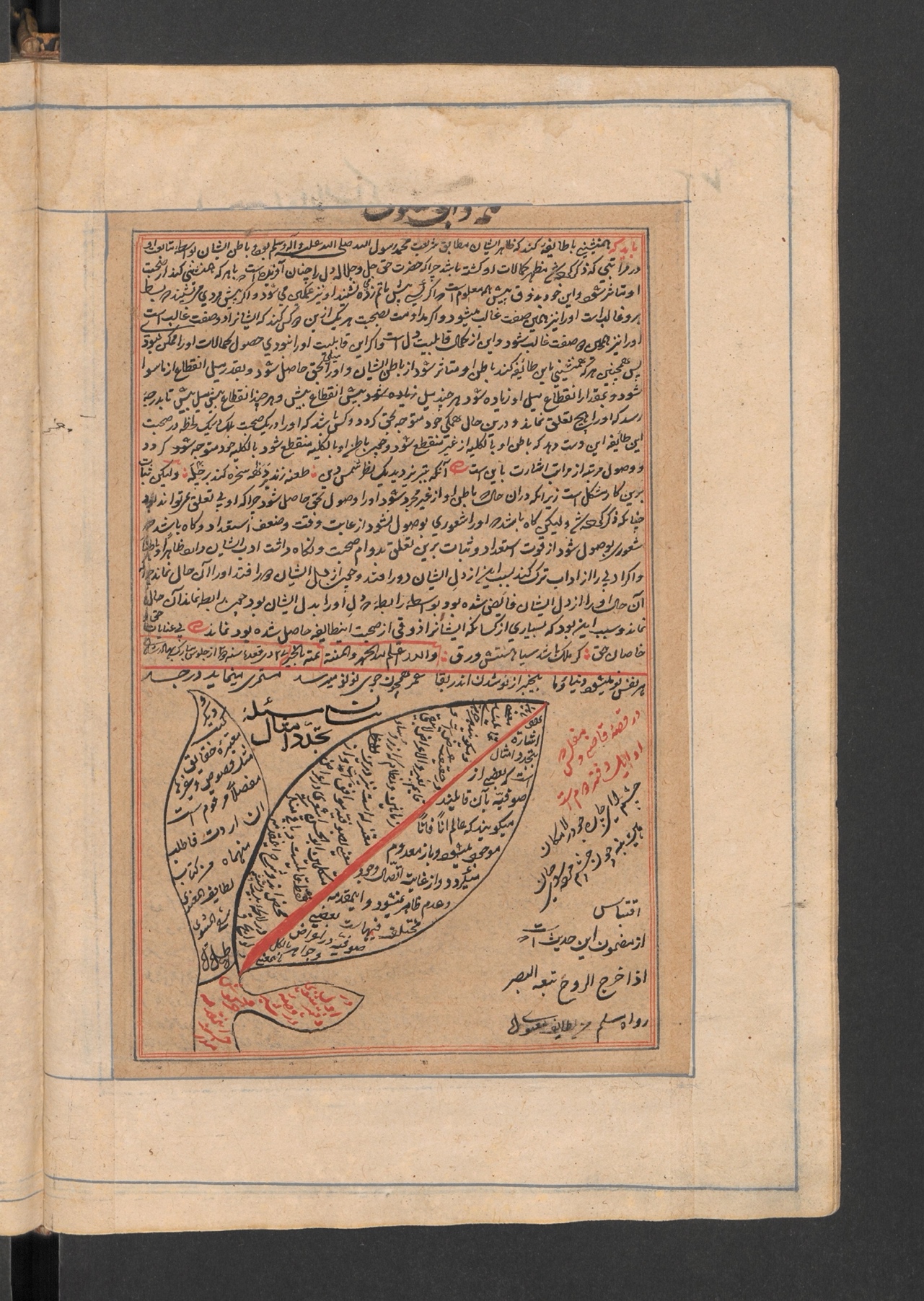

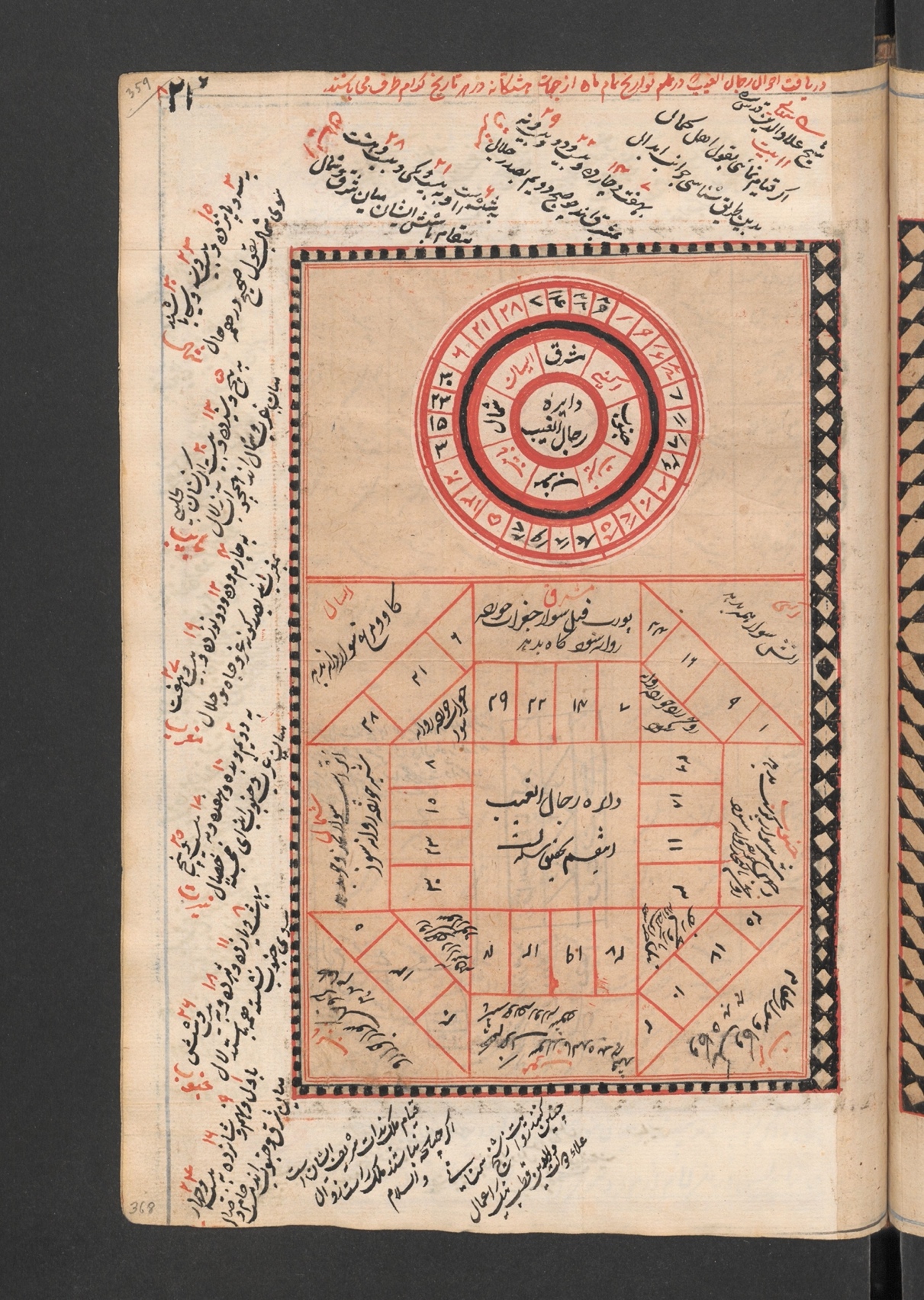

Now, a little more on this manuscript and why we chose it as the focus of what will hopefully be a grant-supported multi-year project. First off, it is a spectacular object, each page carefully crafted for aesthetic impact as well as the conveyance of information (and perhaps more than simply information but other affects and emotional impacts as well). Along with the diversity of hands and calligraphic material, the reader is immediately struck by the many different shapes and arrangements into which blocks of texts have been carefully laid—this is not a case of successive generations of gloss-writers running low on room, but of our compiler (and his contributers, not everything is in his own hand) plotting out the location and shape of texts well in advance, towards ends that are not always intuitive to us and which will require research to untangle.

One thing that is clear from both al-Shaṭṭārī’s introduction and from the texts we have examined thus far is that our compiler/author had a basically autonomous readership in mind—he did not simply compile this work for his own benefit (distinguishing it from majmū’as that are more akin to a personal commonplace book) but intended it to be read by others, to be used as a sort of library of everything that one needed to know. Hence the seemingly rather peculiar spatial layouts we encounter are not excercises in cleverness or intended only for passing visual effect, but have some purpose in guiding and shaping the reader and conveying something that could not be transmitted otherwise. We thus have a potential opening into one part of the longer history of reading in the Islamicate world, from the medieval period in which, ideally at least, readers maintained an oral or aural connection with the author of a text, interacting with texts in an environment of shaykhly instruction conveyed in person, to the ultimate world of print in which the reader could pick and choose among books which he or she read as an effectively autonomous individual, the author’s intervention remaining confined to the pages of the book. The Safīnat, as befits its 18th century composition, seems to represent a transitional point in that historical trajectory, fitting with other trends and transformations taking place not only in South Asia but across the Islamicate world.

At the same time, the Safīnat contains a trove of Persian and Arabic writings that stretches across the centuries, from compositions original to al-Shaṭṭārī himself all the way back to classical texts of literature, akhlāq, sufism, and so forth; many of the “ancient” texts however embedded within frameworks of commentary and annotation, while also representing textual traditions the contents of which might be quite different from other known exemplars. As such this work gives us a window into the textual universe of early modern South Asian Islam, and of early modern Islam more broadly—the texts that were being read, as well as the frames of reception and exegesis.

And because we are primarily interacting with this work in a digital environment, using tools and methods already existing while also considering new ways to explore a spatially complex and challenging work, the Safīnat will provide a testing ground for expanding the reach and scope of Islamicate digital humanities, or so we hope! In a way we are simply extending the genealogy of textual technology within which this manuscript stands, combining innovative approaches at the edge of our technological affordances with old texts and long-established modes of thought and analysis.