One of the most potent affordances of manuscript textual production, as opposed to typographic or digital print, is the simple fact that handwriting permits a lot more variation and even downright weirdness in what ends up on the page. To be sure, speaking generally manuscript production tended to take place within certain socio-cultural limits or norms, scribes following established scripts, layout conventions, and various other elements of convention, all of which are fairly crucial for making one’s written product legible to others. However, even within those broadly acceptable parameters there was, and is to some extent still, a lot of variety in terms of what appeared on the page and what was incorporated into the writing itself. There is no one unitary Arabic script manuscript tradition, but instead many converging and interrelated but distinctive traditions. And to be sure at times the people who made and interacted with manuscripts took decidedly idiosyncratic routes that cannot be explained by reference to existing traditions of practice.

The resulting variety of semantic, and what we might call semi-semantic, signs and marks is a big part of what makes the manuscript tradition so interesting and exciting to explore; but when we set out to transcribe those manuscripts, “translating” them into a typographic or digital environment, we begin to encounter challenges, among them the question of what to do with characters that do not have Unicode representation, and which may be de facto unique, or so infrequent that it would make little sense to go through the process of generating exact digital representation. As we at OpenITI have begun to seriously work through these issues, we have realized that just having a better view of the issue at hand is important—just how much character diversity are we talking about? How do we distinguish what counts as a “character” and other elements incorporated into manuscripts? What ultimately do we need to represent and how?

So, in order to better get a handle on just what we’re up against as it were and to better illuminate the diversity—and sometimes downright weirdness—of the Arabic script manuscript tradition, we’d like to ask you, dear reader, to share examples from your own forays into the manuscript tradition, either via email for us to catalog and to share, or post them on Twitter and tag us (@openiti).

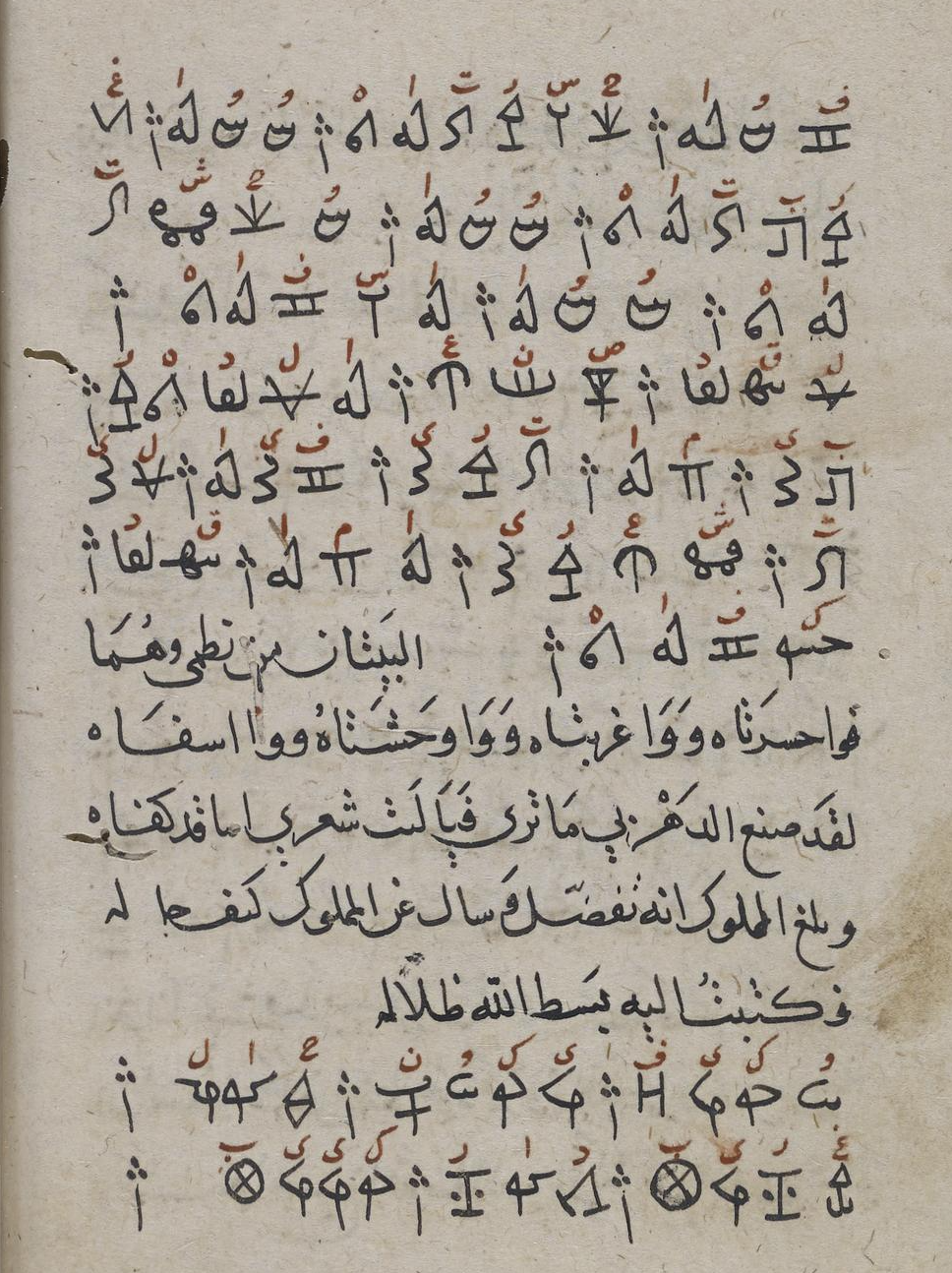

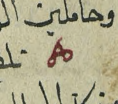

To give you an idea of what we’re talking about and what we’re looking for, here are a few examples that I plucked from a folder of manuscript sample images—not precisely a random selection but pretty close to it. First, one of the more common and intractable sorts of characters that populate many an Islamicate manuscript (and beyond the confines of the tradition—these characters have a very long genealogy that pre-dates Islam and Arabic script both and would develop globally, well into the present) are the letters of “occult” or “magical” alphabets, such as in the following early modern Ottoman example:

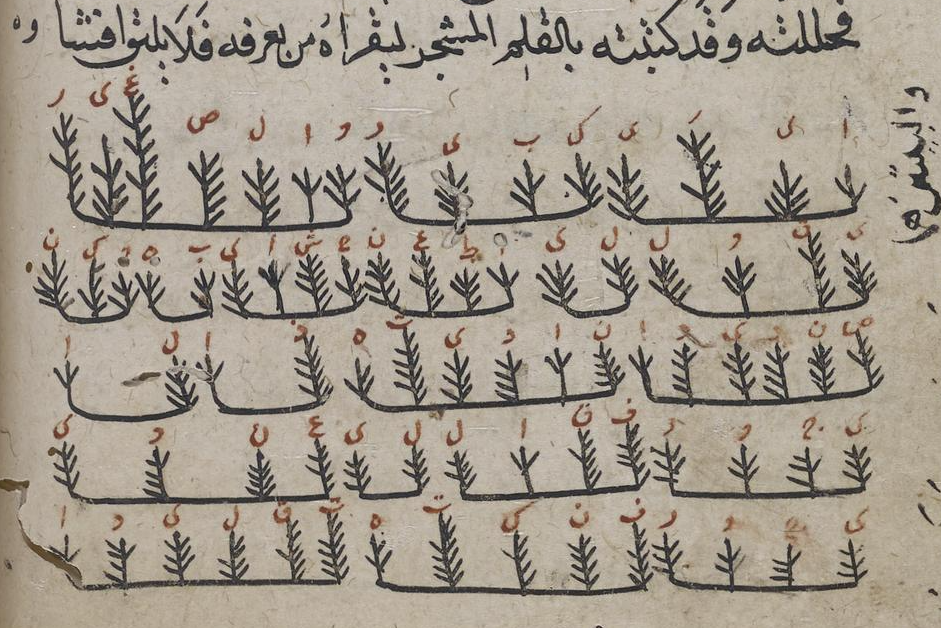

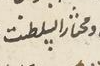

These sorts of characters come in seemingly all shapes and sizes, usually without the clarifying interlinear:

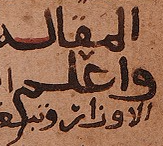

Also frequently encountered across the tradition are marks—to use the most neutral term for what can be quite polyvalent characters—used to indicate things like punctuation, section divisions, and so on (and sometimes, as in the following instances, the exact purpose or purposes are not super clear):

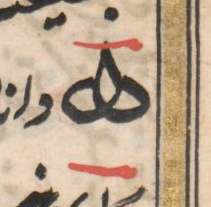

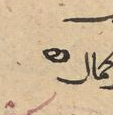

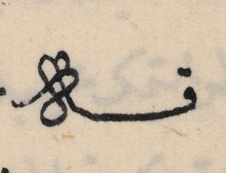

Other things to be on the lookout for: non-standard uses of dots, particularly the various combinations of stacking for adjacent dots, as here:

Or the use of unusual or non-standard orthographic devices:

Or character combinations that might seem to rise to the level of unique characters in their own right:

The above is just a tiny sampling of what we find across the vast ocean of Arabic script handwritten texts—let’s see what all we can find and figure out how we can best interpret these characters both in terms of their historical semantic (or otherwise) significance and in terms of rendering them in a digital transcription environment.