One of OpenITI’s major deliverables in our most recent round of work is the Automatic Collation for Diversifying Corpora (ACDC) project and ensuing tool, which we are now making available for wider use and experimentation: the relevant code and instructions for installation and use are available on Github, and additional data and documentation will be forthcoming. ACDC is one component in our multi-pronged strategy to significantly boost handwritten text recognition for Arabic script as manifest within the manuscript tradition, a tradition of text production that dates from around the time of the Qur’an’s codification all the way down to the present (in some parts of the Islamicate world manuscript production for various purposes remains very much alive!). In this week’s blog entry, I’d like to briefly introduce the project (or, rather, allow one of our other team members do so), then focus on one aspect of its production: the creation of training data via selection of a limited manuscript corpus and then manual transcription of exemplars from that corpus. We’ll see the rationale that lay behind our selections, and in so doing get a valuable glimpse of the immense diversity (and, from a technical standpoint, challenges!) of the Islamicate manuscript tradition, and reflect on the nature of ‘canonicity’ in Islamicate texts and the multiple forms of use that these manuscripts underwent in their ‘working lifetimes.’ We’ll return to ACDC later in the spring semester, as we explore its capacities more and finish documentation and archiving of the relevant data.

Our team member David Smith (Northeastern University), the main driver behind the ACDC project, has just released a video introduction and tutorial to the project and the ensuing tool, wherein he explains the logic of the project and gives a detailed walk-through of use, do have a watch!

Library of Congress PK6450 .G2 1593

Library of Congress PK6450 .G2 1593

My primary contribution to this project was in leading the production of training data: while the goal of ACDC is to limit the amount of necessary training data for the production of valuable HTR through its text alignment method, in order to construct the tool itself some training data was necessary, albeit not on the same scale as our previous work on optical character recognition (thank goodness, as manuscript transcription is a whole other order of difficulty!). Our goal in compiling a training data set was to reflect the internal diversity of the Islamicate manuscript tradition as manifest in particular texts common across the corpus, existing in many copies, and hence especially useful for training the alignment method. We wanted to have script diversity, obviously, meaning texts that could be found from the Maghrib to southeast Asia, but we also wanted a good representation of layout diversity, from multi-column poetry to extensive marginal annotations, many lines per page to a few widely spaced ones, and so forth. This meant identifying and then collecting many examples of texts that obtained a ‘canonical’ status in medieval and early modern Islam (primarily, though not all of these texts were of an exclusively Islamic nature). What do we mean by ‘canonical’ in these cases? Perhaps it would be better to demonstrate via an exploration of the five-text corpus we chose to structure our training data set, as each text became canonical for different reasons, with the manuscripts of these texts displaying the particular forms of use that canonicity involved, and through which it was generated.

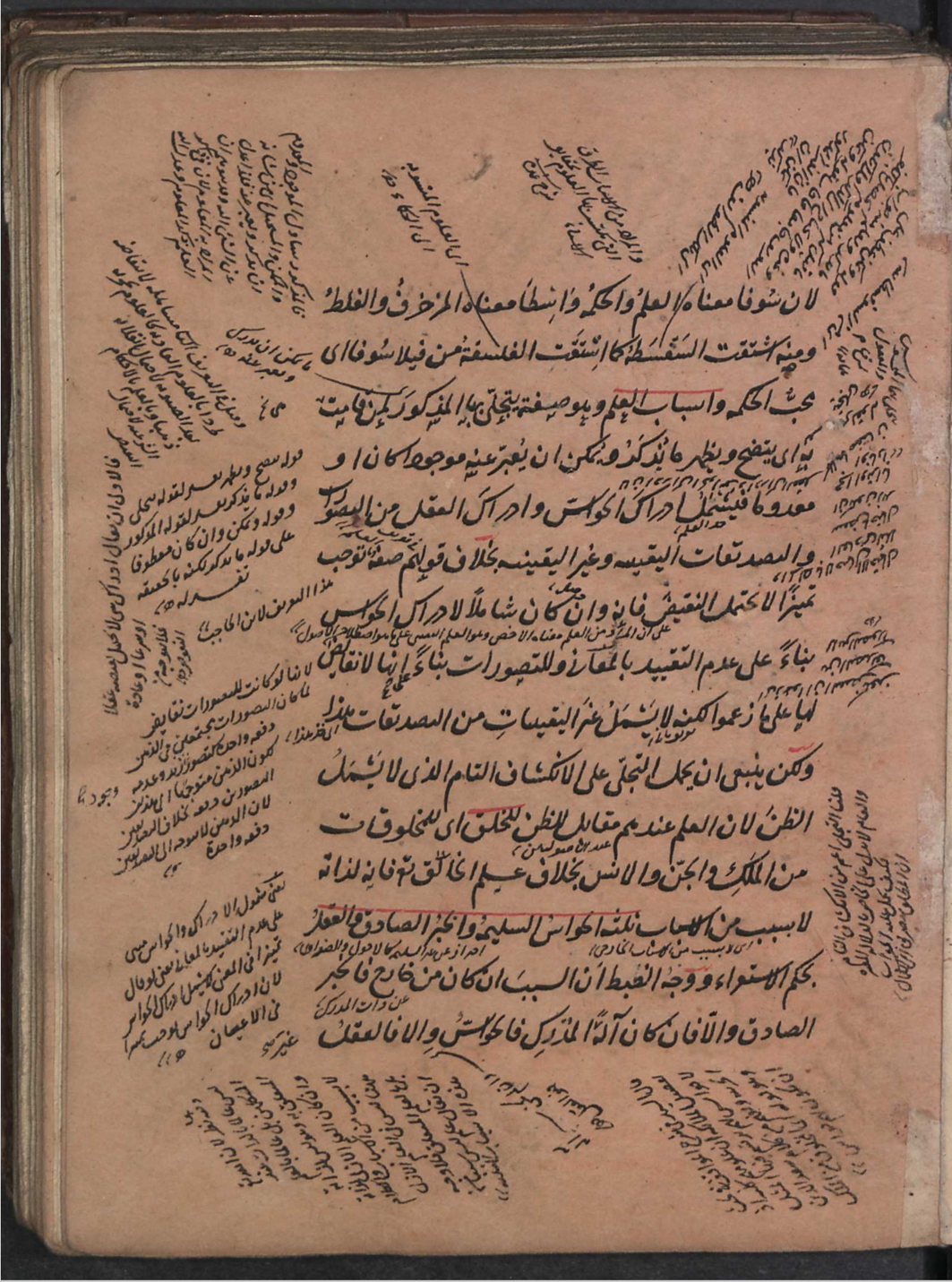

Perhaps the most visually striking text in terms of layout in our corpus comes from copies of Sa’d al-Dīn al-Taftāzānī’s Sharḥ al-ʻAqāʼid al-Nasafīya. One of if not the most important theological introductory texts of the late medieval into early modern Islamicate world, al-Taftāzānī’s commentary on the short ‘aqā’id (‘creed’ as it is often translated, albeit not precisely accurately) text of the medieval theologian Abū Ḥafṣ 'Umar al-Nasafī elaborated further on the principles of Islamic philosophical theology, with many later authors adding their own super-commentaries to al-Taftāzānī’s initial sharḥ. We chose this text not just because it exists in many, many copies, having become a mainstay of madrasa ‘curriculum’ across the Islamicate lands (but especially in the Ottoman world), but also because like many such texts employed in a madrasa context, it is often very complex layout-wise, composed with wide interlinear space and ample margins, both elements designed for additional annotation by students or for the addition of marginal commentary. And like other typical madrasa texts, the overwhelming majority of manuscript copies are decidedly non-prestige, featuring no illumination or decoration, employing scribal hands of a very ‘workaday’ mien, and hence encompassing a great deal of diversity given the chronological and geographic reach of this text.

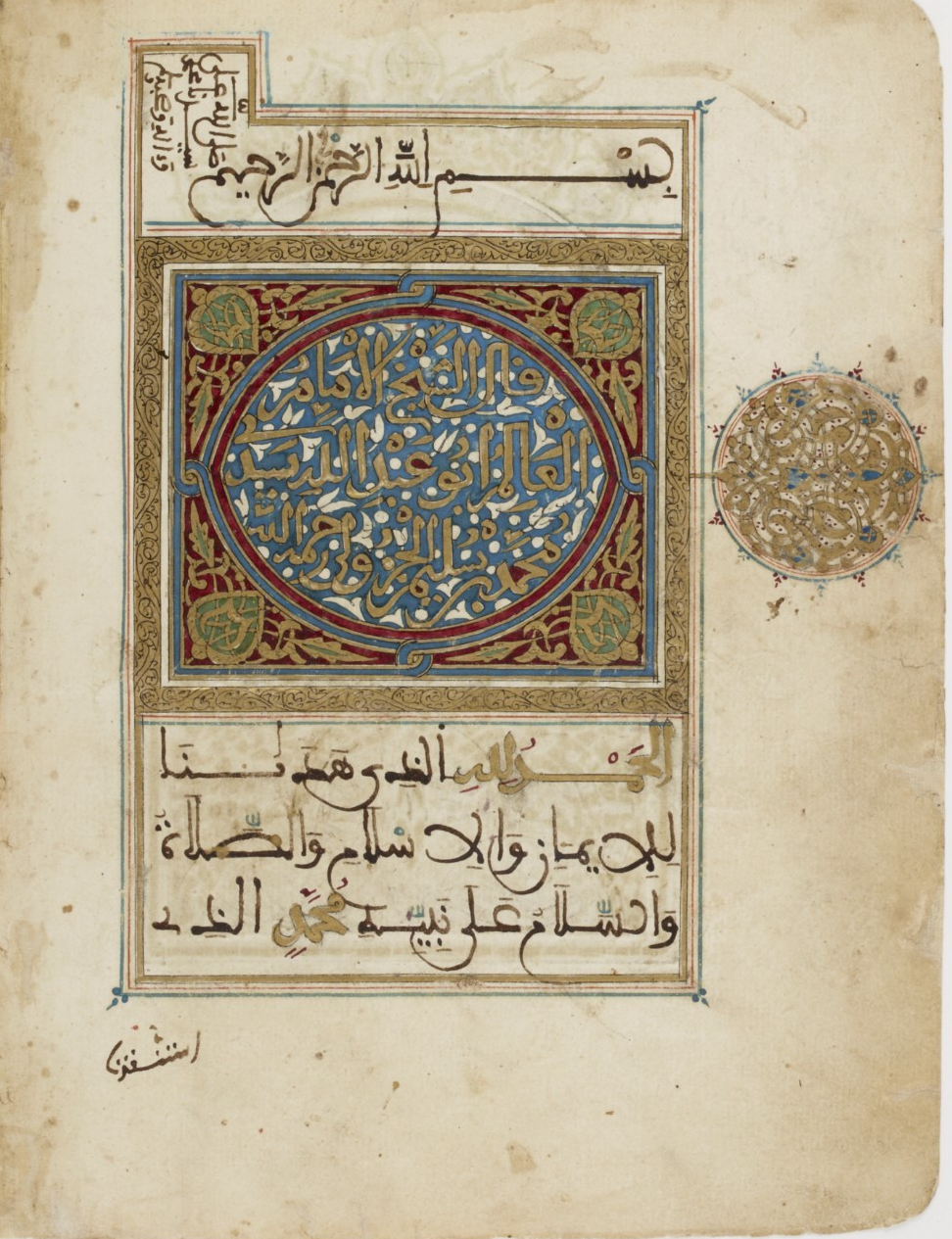

While a widespread text due to its mainstay nature on the madrasa cirriculum, in sheer numbers al-Taftāzānī’s sharḥ is easily overtaken by what might well be the most copied pre-modern Arabic text after the Qur’ān, Muḥammad al-Jazūlī’s prayerbook (not the most apt translation but it will do for the moment) Dalā’il al-khayrāt, perhaps the most important single text in the history of Islamic devotional practice, a importance reflected in the vast number of copies in existence. Alone among the five texts in our corpus, manuscripts of the Dalā’il can be found quite literally everywhere Islamicate manuscripts were produced, from the westernmost edge of Africa all the way to eastern China; while rare in the Iranian lands there are occasional copies. Aside from the Qur’ān it is hard to think of any text with such geographical and chronological reach, ubiquity which is visible in the internal diversity of the text’s manuscript tradition. While naskh predominates as the script of choice, and many prestige copies exist, other scripts and iterations of hands, refined and rough, exist; likewise, while some Dalā’il copies are lavishly illustrated with devotional imagery, many have the bare minimum, and some have no imagery at all. Marginal texts, interlinears, and the like are common, but not universal, given that they are not strictly necessary for the primary uses of this text. Rather, this text functioned as a means of performing taṣliya upon Muhammad and eliciting blessings for the reciter; it also functioned in a physically prophylactic way, akin to talismanic texts or to other, later forms of devotional art and composition. Many of the images of Mecca and Medina, which early on became near universal mainstays of the text, have evidence of tactile engagement: rubbing and kissing, both means of obtaining baraka from these images. As both a driver of and beneficiary of the ‘devotional turn’ of late medieval and especially early modern Islam, the Dalā’il came to occupy by far the most diverse range of physical settings, from modest private homes to the most exalted sultanic libraries and foundations. The relatively rapid movement towards canonicity in this case was facilitated by the proliferation of multiple forms of use for these manuscripts, ranging from public ritual performance to private household reading/recitation to physical presence and tactile participation.

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Arabe 6983

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Arabe 6983

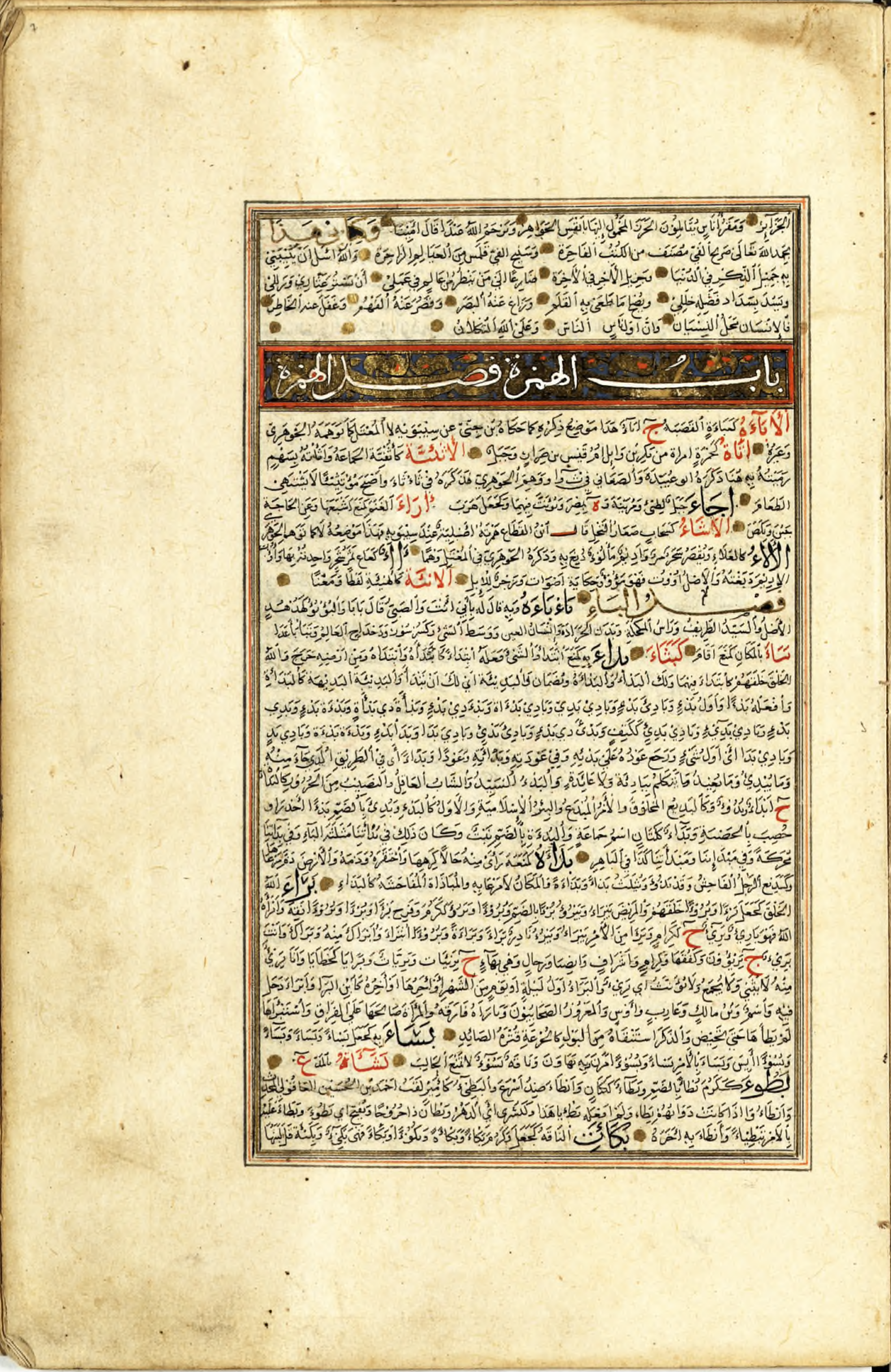

Our third Arabic text represents yet another route to canonicity, in this case not closely tied to Islam qua religion: al-Fīrūzābādī’s truly oceanic Arabic language dictionary, al-Qāmūs al-muḥīṭ. Despite being a massive text, this lexical compendium was widely copied and housed in a surprisingly diverse range of institutions, making its way into Christian libraries as well as those of mosques and madrasas, reflecting shared cultural contours of Arabic culture in the pre-modern world. Its essentially reference work nature can be seen in the layout style: while there are various interesting paratextual interventions built into these copies (larger point sizes to identify the various word entries and the like), there is little to no marginal annotation or other forms of intervention outside of or parallel to the main text. Most notably, the pages of these manuscripts tend to be absolutely packed with text, containing the highest number of lines and words out of our five text corpus; I noted a higher rate of obvious scribal errors, especially reduplication of words and lines, no doubt as a result of the density of text spacing as well as the fact much of the material is linguistically obscure, filled with roots and morphologies of rare occurrence in Arabic literature. It was this comprehensiveness and utilitarian (though not strictly so) cast that helped to make the Qāmūs such a central and pervasive text, despite its semantic complexity and bulk.

University of Michigan, Islamic Ms. 221

University of Michigan, Islamic Ms. 221

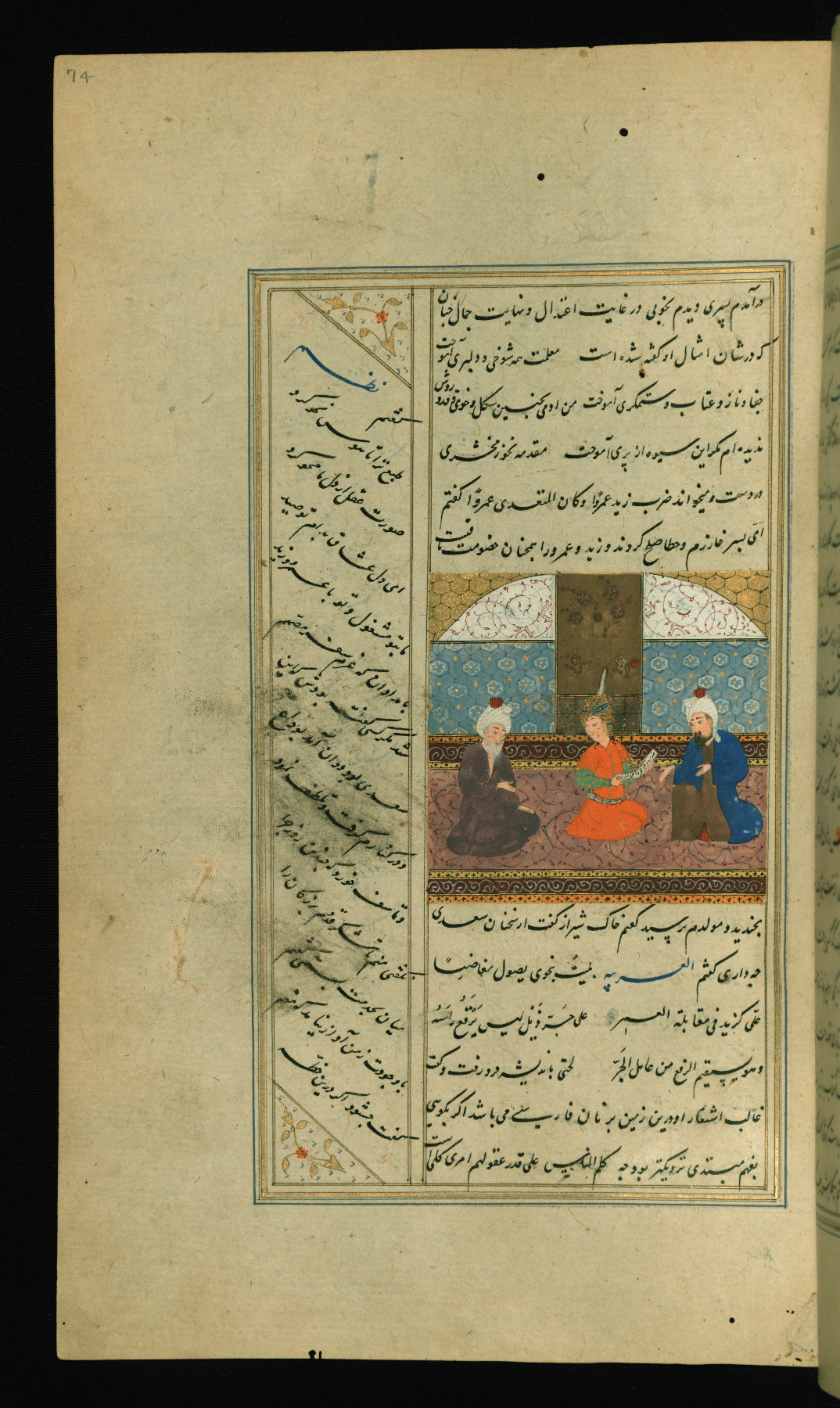

Alongside the previous three Arabic texts we selected two Persian texts (for this project we limited ourselves to those two languages due to the sheer number of manuscripts in both, followed by Ottoman Turkish and, in time, Urdu), one of poetry, the other primarily of prose, both circulating not just in the historically Iranian lands but far beyond in the global ‘Persianate.’ Especially redolent of the far reach of Persian and its status as a language of cultivation is the famous Gulistān of Sa’dī, a broadly moralistic work of stories and lessons, written in what we might describe as poetic prose. Its canonical status was generated not just by appreciation for its contents and their moral instructional value but even more by the utility of this text for learning Persian. As such many surviving manuscripts have a similar layout to copies of al-Taftāzānī’s sharḥ, reflecting, if not a madrasa context, something very similar in Persian language learning environments (which might have taken place in a sufi tekke or in the private home of a scholar, less often in madrasas themselves). Interlinears in Ottoman Turkish are especially common, as this was the primary text for the learning of Persian among Turkish speakers in the early modern world. Unlike al-Taftāzānī’s sharḥ, prestige copies of the Gulistān also exist, as its canonicity, while underlined by its pedagogical role, was more broadly based. It was a text that graced the libraries of the elite, and thus attracted extensive illumination and illustration programs, examples of which we included in our data set.

Walters Art Museum, Walters Ms. W.617

Walters Art Museum, Walters Ms. W.617

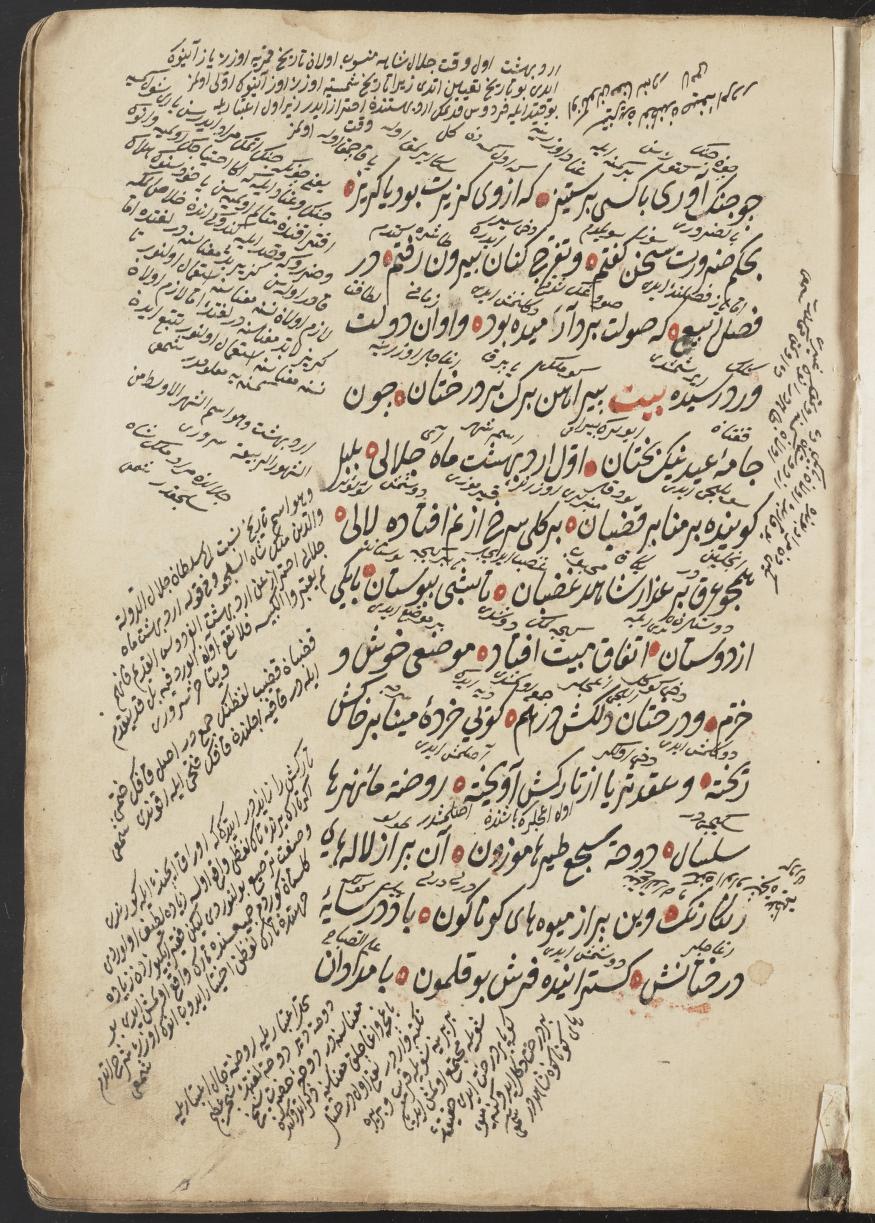

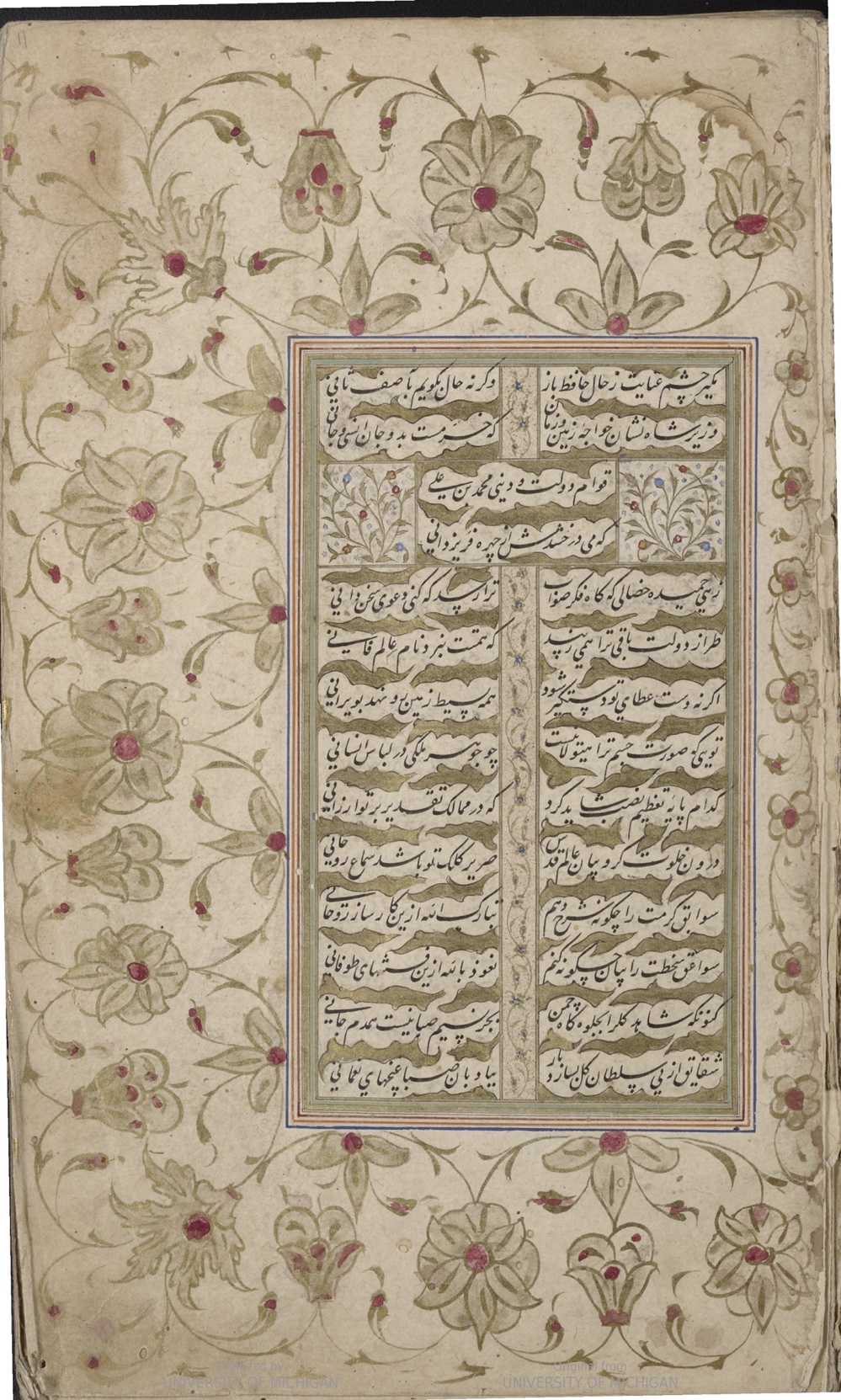

Finally, in order to represent the Persian poetic tradition, we selected one of the most famous and deeply culturally embedded compilations of Persian poetry, the Dīvān of Ḥāfiẓ, a work with especially powerful resonances in the Iranian lands, though it too like the Gulistān circulated far beyond Persian-speaking regions and was a central element of wider Persianate culture. Much like Dalā’l al-khayrāt, the Dīvān would become something of a household fixture, and not just among the elite, often acting as an object of festive bibliomancy, a role it still occupies today in fact. In terms of layout features, the Dīvān is a good example of the use of ‘pseudo-columns’ in Islamicate poetry: columns that are primarily aesthetic, as they read continuously across the page (and so unlike several other linguistic/script traditions in the wider Islamicate world, such as Syriac or Ge’ez, in which true columns were the norm, even in prose). These pseudo-columns, often broken in two with illumination, pose real challenges to layout models and particularly to line extraction, issues among others we are continuing to work on resolving. The Dīvān also frequently features slanting text blocks and other complicated features, part of a general transformation towards greater complexity and proliferation of features that we see across the Arabic script manuscript tradition from the late medieval period forward, culminating in anthology-style texts with smply absurd numbers of discrete text blocks arranged, puzzle-like, onto a single page. None of our samples from the Dīvān tradition have quite that level of complexity, but all have at least some of the distinctive features that came to be associated with poetic—especially Persian poetic—texts.

University of Michigan, Islamic Ms. 316

University of Michigan, Islamic Ms. 316

All of these texts posed their own particular challenges in terms of transcription and layout analysis, with the latter an especially tricky continuing issue. Speaking personally, navigating a very wide range of scripts and hands was not always easy, though the fact that we were working on fairly stable canonical texts certainly helped, since I could have reference to other manuscript copies to help clarify paleographic difficulties (the question of textual stability and its relationship, or lack thereof, to canonicity is a whole other matter for another time). And while the data set we assembled is indeed diverse, drawn from across time and space, there are still limitations: virtually all of the material is of early modern provenance, for instance, even though all of the texts are strictly speaking of a medieval date in terms of composition. Because of our focus on specific texts for alignment between multiple copies, we did not include majmū’as with their often distinctive styles of layout and manuscript hand features; while overall legibility certainly varied within our corpus none had the, for lack of a better term, scrawly cast so common in majmū’as, intended as many of them were for largely person consumption. In recognition of those limitations we later developed an extensive evaluation set, pulling from all manner of texts, periods, styles, and so forth, including those under-represented or not represented at all in our training data set; perhaps aspects of that work will feature in a future blog post.

It's also worth noting that we drew upon a somewhat restricted range of digitized manuscript repositories due to download restrictions: everything in this particular data set has been taken from sources that permit full downloads of digitized texts, either via PDF, IIIF, or individual image formats. This precludes repositories such as the British Library or the Hill Manuscript Museum and Library which, for varying reasons, prohibit or restrict downloads, requiring in-domain viewing. We also decided to exclude downloaded material available to us that was not of a strictly licit nature—meaning, primarily, the widely circulated digitized contents of a certain major manuscript collection in the former capital of the Ottoman Empire. Because everything we incorporated is freely available, we will be able to make every aspect of our data openly available once we are finished archiving everything (I’ll update here with links once that process is complete). Limitations in repository availability (and coverage) meant that some regions were definitely under-represented: while we were able to draw upon some West African material via the Bibliothèque nationale de France, the considerably larger digital archives from the region were not available to us for this project; East Asian material was also lacking, due to its limited digitization. And in retrospect, I should have scoped out more Southeast Asian material, much of which is available (with a great deal more contained within in-domain only viewing repositories).

Finally, a personal note: it was a real pleasure (well, most of the time) compiling and transcribing the two manuscript data sets that went into this project, as it involved exploring corners of the Islamicate manuscript tradition I had not really seen before. Unlocking more and more of the diversity of this vast tradition is one of the primary goals of OpenITI, encouraging and enabling more people to navigate these riches and to make use of what is contained therein; if tools like ACDC help to encourage manuscript exploration and use even a little then we will count that as a step forward in the right direction.