Today’s guest post introduces the multi-witness manuscript work of another of our summer paleography and codicology course students, Modje Taavon.

___________________________

Layla, you’ve got me on my knees

Layla, I’m begging, darling please

Layla, darling, won’t you ease my worried mind

“Layla,” Derek & The Dominos (1970)

___________________________

i. Introduction: Niẓāmī Ganjavī’s Laylī-u Majnūn

Niẓāmī Ganjavī’s Laylī-u Majnūn is a twelfth century long-form narrative Persian poem, adapted from the seventh century Arabic story “Majnūn-Laylā” or “Qays-Laylā”. It is the third of five poems which make up Niẓāmī’s Khamsa or “Quintet,” also known by the title Panj Ganj, “The Five Treasures,” and it is made up for about 4600 distiches. Laylī-u Majnūn is a tragic romance about the doomed love between a couple whose fathers disallow their union. As Majnūn’s intense love for Laylī consumes him, he descends into madness and Niẓāmī’s poem explores themes of love, longing, and the struggles between personal desires and societal norms. More importantly, Laylī-u Majnūn is a layered tale that is also a Sufi allegory, reflecting themes such as the annihilation of the self, the rejection of worldly attachments, longing and separation, and union and ecstasy. If the broad strokes of the sentiments behind Laylī-u Majnūn seem familiar, it is no doubt because Niẓāmī’s treatment of the tale forms the basis of Eric Clapton’s song “Layla”—the iconic riff and Clapton’s lyrics a modern-day re-telling of Majnūn’s longing for his Laylī.

The death of Laylī and Majnūn, Bodleian Library MS. Elliot 192, fol. 150a.

The majority of the copies of Niẓāmī’s Laylī-u Majnūn that I have come across do not exist as stand-alone works—instead, they are contained within the Khamsa. Niẓāmī’s poem is one of the most commonly copied examples of Classical Persian poetry and the number of extant manuscripts is a testament to this fact. The Union Catalogue of Manuscripts from the Islamicate World alone lists 28 manuscripts from Southwest, Central, and South Asia, ranging from the fifteenth through the eighteenth centuries. The most interesting aspect of a text such as this is that as widespread as it is, there is a great deal of variation. The three witnesses I am employing show a great deal of shifting of sections, inversions of lines, and the like.

ii. Witnesses of Laylī-u Majnūn

This summer, I selected three digitized manuscript copies of Laylī-u Majnūn: an early sixteenth century manuscript held by Oxford’s Bodleian Library (MS. Elliot 192), an early eighteenth century manuscript held by the State Library of Berlin (SzB Ms. or. fol. 107), and an early nineteenth century manuscript held by the Library of Congress (LoC M19). MS. Elliot 192 contains a date statement in the colophon written in Arabic: “Saturday, 22 al-Muḥarram al-ḥarām, in the year 907” [17 August 1501 CE] and the scribe’s name is given as al-Shīrāzī. The inside front cover of SzB Ms. or. fol. 107 has extensive notations in Latin and Persian (but written in Arabic in a script that seems almost a Maghribī naskh). The inscriber notes the date of this manuscript as 1041 Hijrī / 1631CE, but this contradicts the date statement in the colophon which states the work was completed on “19 Jumādaā al-ʾawwal in the year 1121,” suggesting the corresponding Gregorian date is 1709. The colophon is written in Persian, but there does not seem to be a scribe’s name. LoC M19 is a disbound manuscript with a number of ownership stamps and perhaps owners’ notes, in addition to other notes in the opening pages before the Khamsa begins. There are also notes on the endpapers and the text contains a number of marginal notations which seem to be corrections or emendations to the main text. There is a colophon for each section of this witness of the Khamsa; the colophon for Laylī-u Majnūn contains a date statement of “26 Jumādaā al-thanī in the year 1220” [20 September 1805 CE].

All three manuscripts are written in a nastaʿliq hand, contain miniature paintings and illustrations, and seem to be prestige copies of Niẓāmī’s Khamsa. For the purposes of this workshop, I opted to transcribe the first five chapters or sections of Laylī-u Majnūn. I was curious to see whether the sections that are typically considered part of the ‘prologue’ of a long-form poem such as this may offer interesting degrees of variation, just as there is great variation seen in the prologues of various extant copies of Ferdowsī’s Shāhnāmeh. Because art by definition is an interpretive genre, I knew any manuscript of Laylī-u Majnūn would necessarily contain a high degree of variability, but I wanted to generate specific evidence as to what kind. Would the variation stem from the scribe’s idiosyncrasies? That is, his particular hand, the method by which he copied his text (e.g. from another manuscript, or was he transcribing from an oral declamation), the reign under which he was employed, his geographical location. Alternatively, are these variations a reflection of the transmission history of Laylī-u Majnūn at large across the Islamicate and Persianate worlds, beyond a local context? Likewise, I was curious to investigate the degree of variability of the manuscripts themselves as physical objects—their bindings, their media, and even their layout. How might attending to the aesthetics and visual logic or grammar of a work expand our understanding of the history of transmission and circulation of that work—of how people engaged and interacted with Laylī-u Majnūn over the years?

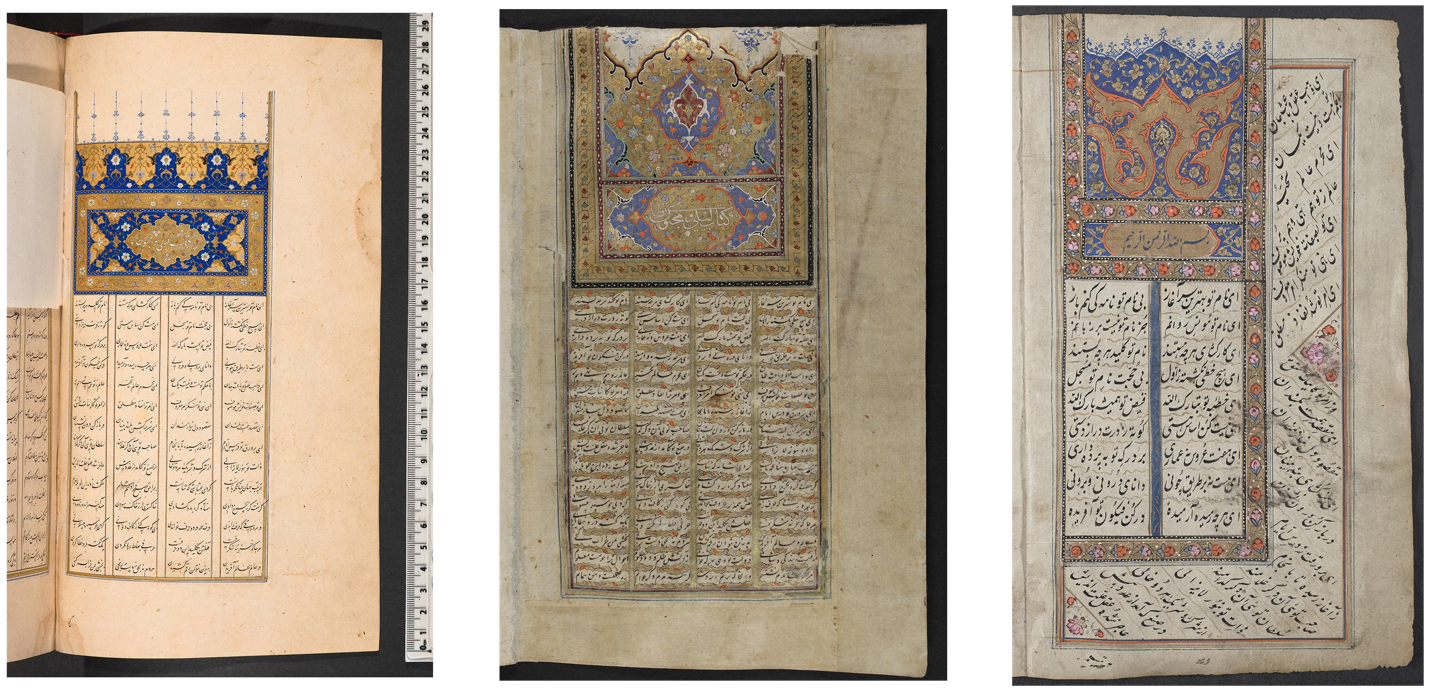

Three witnesses are perhaps not enough of a sample size to really answer any of my initial questions, but they do begin to demonstrate a pattern of variation, even in the first five chapters. For example, all three of my witnesses feature Laylī-u Majnūn as the third text in the Khamsa, so there is a stable order of the individual texts within Niẓāmī’s Khamsa. All three witnesses of Laylī-u Majnūn have a tāj, or frontispiece, at the very start of the text, despite the fact that there is a slight difference in layout.

From left: MS. Elliot 192 from the Bodleian Library, SzB Ms. or. fol. 107 from the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, and LoC M19 from the Library of Congress.

From left: MS. Elliot 192 from the Bodleian Library, SzB Ms. or. fol. 107 from the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, and LoC M19 from the Library of Congress.

Two of the three witnesses—MS. Elliot 192 and SzB Ms. or. fol. 107—are written in four columns, a very common layout for Persian poetic works. The third—LoC M19—is in two columns with a third wrapped around the margins. The number of lines per page differs across all three manuscripts, no doubt owing to the different dimensions of each. These conventions of visual grammar of how poetic works are presented seem to me to be a precursor to the stability afforded by print which Dr. Jonathan Parkes Allen discusses here.

iii. Transcribing Laylī-u Majnūn

Our main task this summer was to manually record, as diplomatically as possible, a multi-witness transcription of a particular work. Using eScriptorium, I began to transcribe the first five chapters of Laylī-u Majnūn and determined that there are three types of variation observable in at least these witnesses of the work: orthographic variation, variation at the word level, and variation in the presence or absence of several lines, if not entire sections at a time. Orthographic variation is sometimes a matter of the idiosyncrasies of the scribe’s hand—different ways of writing the final ya, for example, or alternating between different forms of the initial ha form in the same manuscript.

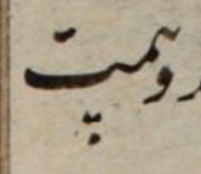

Transcription, I have come to learn, is more an art than a science—closer to Duane Allman’s brilliant translation of Majnūn’s yearning onto the slide guitar or Rita Coolidge’s piano coda that sounds like what the ecstasy of unity must feel like for Majnūn. The major difficulty I faced was how best to transcribe diplomatically (i.e. to render the paleographic hand into Unicode as closely and precisely as possible). Take, for example, the following screenshot of the word «بیمت» [bīmat] in MS. Elliot 192. To transcribe this as diplomatically as possible, one would render it as «ٮپمت», even though the consolidation of dots is an aesthetic choice and not an orthographic one. If one were to reverse transcribe the diplomatic transcription, however, it would go from bīmat to ?pmat, losing all semantic meaning. There is a danger of being so diplomatic as to render a transcription utterly useless unless it is to be presented alongside the digitized manuscript. What does diplomacy even mean in such a context? How do we decide the best way to transcribe diplomatically without sacrificing semantic accuracy?

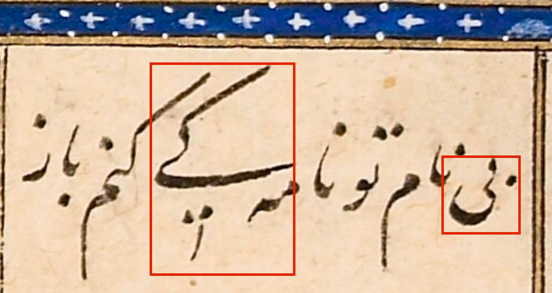

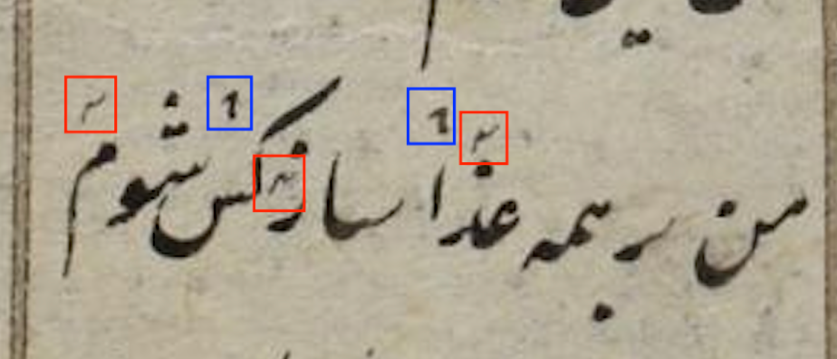

Another important area of focus is recording instances of scribal corrections. During the course of our studies, Dr. Osama Eshera taught us to recognize the way scribes often index corrections, like the one seen here from SzB or. fol. 107 on fol. 91v. There are two sets of sigla. The ([^۲]dir=”rtl”}) highlighted in red marks a transpositional error: the scribe has written «من بر همه غذاساز کس شوم» but the line should read «من بر همه کس شوم غذاساز». The second set of sigla (marked in blue) seems to be a dotless (خ) which may either indicate a variant reading or another way of noting a transpositional error.

iv. Collating Laylī-u Majnūn

The initial collation suggests that while there is a great degree of variability between the three witnesses of Laylī-u Majnūn employed here, the variability occurs along a similar matrix. By this, I mean that it is often the same sections that shift, the same words that change, and the same orthographic features that index the scribe’s idiosyncrasies. Quite surprising to me is that the two witnesses that are the furthest apart chronologically—MS. Elliot 192 and LoC M19—are almost identical. Though there are no definitive indications of where these manuscripts were copied, it seems likely that LoC M19 was copied in India while MS. Elliot 192 and SzB or. fol. 107 are from southwest or central Asia. As I continue my research, I look forward to the possibility of tracing out the genealogy of these manuscripts, working towards a stemmatological analysis of extant witnesses of Niẓāmī’s Laylī-u Majnūn.

______________________________

Modje Taavon is a doctoral student in the Program for Comparative + World Literature and the Program for Medieval Studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Her research focuses on medieval and early modern Persian, Arabic, and English advice literature, and its participation in political and ethical debates.